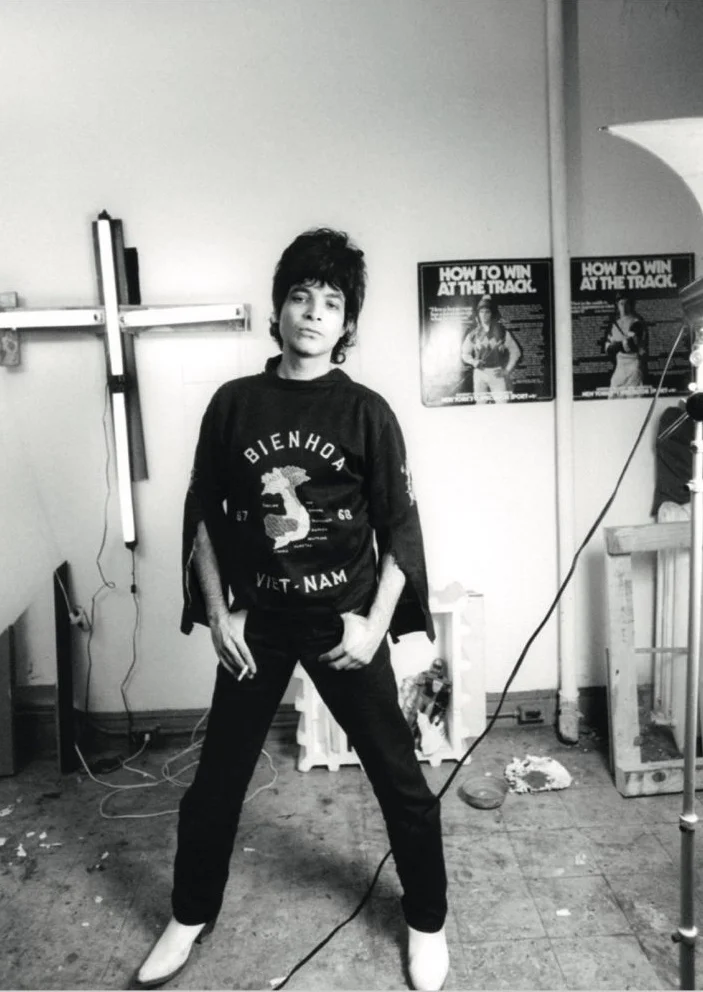

ALAN VEGA

Born in Brooklyn, Alan Vega was reared on the rock ’n’ roll sound of Elvis Presley and Roy Orbison, but originally struck out on a career as a visual artist and light sculptor, making pieces out of electronic debris. But on the occasion of seeing Iggy Pop fronting The Stooges at the New York State Pavilion in 1969 was an epiphany for Vega. “It showed me you didn’t have to do static artworks, you could create situations,” he said. “That show was the first time in my life the audience and the stage merged into one.” It was that eradication of barriers between the two that Vega took to heart.

Rather than rely on classic rock ’n’ roll instrumentation, Vega's duo, Suicide, along with Martin Rev, assaulted ears with little more than Rev’s Farfisa organ and gutted drum machines and Vega’s terrifying, in-your-face growl. They mauled audiences during their heyday and were a paradigm shift to numerous generations of musicians the world over. Hardcore punk and synth-pop, industrial music and techno, even rock ’n’ roll itself, were all swayed by the gravitational pull of Suicide. In no uncertain terms, Suicide encouraged the likes of Bruce Springsteen, Nick Cave, Björk, M.I.A., Nine Inch Nails, Depeche Mode, R.E.M., LCD Soundsystem, Savages, Pet Shop Boys, Dead Kennedys and Daft Punk, to name just a few, to fearlessly realize their own vision.

Suicide came to be seen as the ultimate in audience confrontation and rock nihilism, even if the group also sought to accentuate the ‘life force’ of this world as well. “[Suicide] were about recognizing how alive things were,” Vega said. “When it came to our live shows, we didn’t want to entertain people. We wanted to throw the meanness and nastiness of the street right back at the audience. Some nights we’d barricade the doors so they had no choice but to stay and listen. Every night was like fighting a revolution.”

Their first two albums, 1977’s Suicide and their 1980 follow-up, remain two of the era’s greatest touchstones, beacons for others seeking to transform their worlds with sound. And even during the group’s hiatus through the 1980s, Vega continued to pursue his singular vision across an individualistic solo output. From his 1980 self-titled debut and rockabilly-infused albums like Saturn Strip, through bracing albums like Power On to Zero Hour and IT, Vega forged his own singular path.

For all the darkness and despair that encompasses this moment in our world – and despite his work being depicted as bleak and nihilistic – for Vega there was always a sense of hope and a place for dreams to become reality. “People have always told me that my music is angry,” he said. “To me, it was always just an energy. It was the way I perceived the world. The key Suicide song was ‘Dream Baby Dream,’ which was about the need to keep our dreams alive. I knew back then that something poisonous was encroaching on our lives, on all our freedoms.” He fights to his very last breath for that freedom on IT, his last will and testament, one that cements Vega’s legacy as a seer: “People have always said that my work was ahead of its time. But I’ve always believed it’s been right on time.”